May 2021 Timeline

Ironfoot Jack

an essay by Colin Stanley

Jack Rudolph Neave was born in Sydney, Australia on November 4, 1881. His parents were English and his mother always dreamed of returning to England. In 1891 she got her wish when, with Jack and his father, she set sail for London. His father, however, had other ideas, because he jumped ship when they docked at Marseilles and Jack and his mother were forced to complete the journey without him. They lived with Jack’s maternal grandparents in London until his mother unfortunately died just one year later in 1892. His grandparents, who had not approved of their daughter’s choice of husband and had never taken to young Jack, wasted no time in placing him in Walworth Boys’ Home on March 16, 1893, when he was just 11 years old.

Unhappy there, he absconded and hit the road where he was befriended by gipsies and other travellers, making himself useful by helping out at fairgrounds and markets. He told fortunes using a system of numerology, sold charms and performed as a strong man and an escapologist to make ends meet, touring seaside resorts all around the country until about 1909 when, in frustration, after several run-ins with the local authorities, he threw his chains and straitjacket into the sea at Blackpool.

Unhappy there, he absconded and hit the road where he was befriended by gipsies and other travellers, making himself useful by helping out at fairgrounds and markets. He told fortunes using a system of numerology, sold charms and performed as a strong man and an escapologist to make ends meet, touring seaside resorts all around the country until about 1909 when, in frustration, after several run-ins with the local authorities, he threw his chains and straitjacket into the sea at Blackpool.

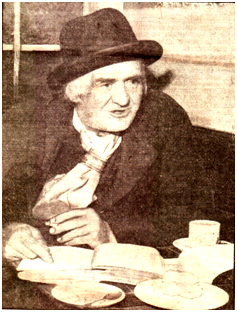

Around 1909 Jack apparently suffered the accident that left him disabled with one leg shorter than the other. Some have contested this saying that his leg was merely shrivelled and the foot still attached. Jack didn’t help matters by inventing more and more ludicrous scenarios to explain how he lost the foot: for example he may have been shot in the leg whilst smuggling, or bitten by a shark when pearl-diving, mauled by a lion on safari, attacked by a rampant bloodhound, trapped under a boulder or run over by a vehicle when heroically rescuing a child playing in the street. Whatever the truth may have been, a windfall came his way, enabling him to purchase a caravan and pony and travel the highways and byways plying his trade as ‘Professor Curio, Lecturer in Astrology, Evolution and the Occult Sciences.’ This windfall also furnished him with the surgical boot with an iron extension below the sole, long black theatrical cloak and wide-brimmed hat that became a trademark for the rest of his days.

With a woman called Zenobia in tow, he travelled around the fairgrounds exhibiting home-made ‘Marvels of the Universe’ in a side-show. This included the amazing ‘Mer-Monkey’, a shark’s backbone, chimpanzee’s skull and assorted animal bones crudely wired together and stained brown to give the impression of age, described by Jack as “The Greatest Scientific Marvel of the Age, the ‘missing link’: proof that man evolved from the animals”. Zenobia, covered in paw-shaped spots, stencilled onto her body using a cork dipped in iodine, became ‘The Incredible Leopard Woman’.

The journalist Hubert Nicholson (1908-1966), as a young boy, recalled witnessing this ‘phenomenon’ in his 1941 autobiography Half My Days and Nights: the autobiography of a reporter:

One year (I was perhaps about nine) there was a side-show I longed to see. I do not know why, or what I expected. It was called “The Leopard Lady”, and I begged my mother to let me go. She gave me the twopence and stood outside

With a woman called Zenobia in tow, he travelled around the fairgrounds exhibiting home-made ‘Marvels of the Universe’ in a side-show. This included the amazing ‘Mer-Monkey’, a shark’s backbone, chimpanzee’s skull and assorted animal bones crudely wired together and stained brown to give the impression of age, described by Jack as “The Greatest Scientific Marvel of the Age, the ‘missing link’: proof that man evolved from the animals”. Zenobia, covered in paw-shaped spots, stencilled onto her body using a cork dipped in iodine, became ‘The Incredible Leopard Woman’.

The journalist Hubert Nicholson (1908-1966), as a young boy, recalled witnessing this ‘phenomenon’ in his 1941 autobiography Half My Days and Nights: the autobiography of a reporter:

One year (I was perhaps about nine) there was a side-show I longed to see. I do not know why, or what I expected. It was called “The Leopard Lady”, and I begged my mother to let me go. She gave me the twopence and stood outside

while I went in. It was late afternoon, October twilight, and the tent was empty, except for a pale woman in a purple robe who was vomiting horribly on to the ground. I stood and stared. Out of the shadows came a man with waist-length black hair, a black cloak flapping like wings, a cravat, ringed fingers, piercing eyes and a short leg with an iron extension clamped to his boot.

“What do you want?” he said.

I was really frightened, but I had paid my twopence and as a good Yorkshire boy I was not going out till I had seen what I went to see.

“The Leopard Lady,” I answered.

He spoke to the woman, in a showfolk’s jargon, that I did not understand. She pulled herself together, wiped her mouth, un-fastened her robe.

I saw a lot of flesh, all marked with yellow-brown spots in roughly the form of an animal’s paw-marks. The showman said something about the woman’s mother having been frightened by a leopard. I concluded he meant something unmentionable; and also that it was not true. As a show it disappointed me greatly; as a glimpse of a life I could only darkly conjecture, it haunted me like a nightmare for years.

As soon as I had looked and been invited to touch her spotted limbs, the Leopard Lady folded her purple robe round her again and went back to the business of being sick. I hurried out of the tent and was promptly sick also.

That was my first meeting with Ironfoot Jack, whom I was to know later in Soho as a kindly and fascinating character…

When Zenobia decided that enough was enough and absconded, Jack abandoned the fairgrounds and headed for London to live in a garret on the Gray’s Inn Road. He became a Hyde Park orator and toyed with the idea of joining an anarchist-communist group. At one of the meetings he was staggered to discover that his long-lost father was the speaker. When the latter disowned him for a second time it was a shattering blow. It ended his association with the anarchists and heralded a dark period in Jack’s life when he became virtually a down-and-out.

Around 1915, however, he fell-in with a well-off widow by the name of Mrs Balbus and was persuaded by her to found a new religion called ‘The Children of the Sun’. Initial meetings were held at her house but as the congregation grew a basement flat was acquired in Charlotte Street in the West End. When this was disbanded he retained the flat which became the home of ‘Professor Curio’s School of Magic’. Entrance was free with nightly lectures and refreshments. The manageress was Mrs J. Neave, Jinny, who he had met when they were sheltering from an air raid during the First World War, and married around 1924.

Jack’s great philosophical mantra, which he adhered to rigidly throughout his life, was that he “worked to live and did not live to work”. Mark Benney, in his 1939 biography of Jack entitled What Rough Beast?, described some of the many and various ways he employed to, as Jack put it, “solve the problem of existence” at this time:

He bought and sold all manner of objects, he read horoscopes, he tipped horses, he interpreted dreams, he hawked cough-cures, he made cheap jewellery, he blended scents. He was to be found conducting credulous strangers on tours through London’s “night-life”; or lecturing, with the aid of a bored chimpanzee, on Evolution and Mormonism. For a short while he drove a flourishing trade in vanishing ink, which he sold to aspiring crooks with the advice that they use it to sign hire-purchase agreements. Again, he had a temporary phase of prosperity when he hit upon the idea of advertising in low journals the sale of “The World’s Most Daring Book on Problems of Sex and Marriage—By More than a Hundred Eminent Authorities”: his description of the Holy Bible which enabled him to sell by mail-order, at five hundred per cent profit, a job-lot he had picked up from a bankrupt missionary society.

The author Pip Granger whose father at one-time rented a flat above the 2I’s coffee bar in Old Compton Street, provided further examples of Jack’s ‘cons’ in her memoir Up West:

He advertised for people to send ten bob…to receive the secret of making money ‘by return of post’. When he got an enquiry, he’d reply promptly with the advice: “Do what I did!” Another scam was to advertise his patent fly killer. Again, on receipt of five shillings …he’d post back two small blocks of wood, one marked ‘A’ and the other ‘B’ and instructions to “Place the fly on block A and whack it hard with block B.”

“What do you want?” he said.

I was really frightened, but I had paid my twopence and as a good Yorkshire boy I was not going out till I had seen what I went to see.

“The Leopard Lady,” I answered.

He spoke to the woman, in a showfolk’s jargon, that I did not understand. She pulled herself together, wiped her mouth, un-fastened her robe.

I saw a lot of flesh, all marked with yellow-brown spots in roughly the form of an animal’s paw-marks. The showman said something about the woman’s mother having been frightened by a leopard. I concluded he meant something unmentionable; and also that it was not true. As a show it disappointed me greatly; as a glimpse of a life I could only darkly conjecture, it haunted me like a nightmare for years.

As soon as I had looked and been invited to touch her spotted limbs, the Leopard Lady folded her purple robe round her again and went back to the business of being sick. I hurried out of the tent and was promptly sick also.

That was my first meeting with Ironfoot Jack, whom I was to know later in Soho as a kindly and fascinating character…

When Zenobia decided that enough was enough and absconded, Jack abandoned the fairgrounds and headed for London to live in a garret on the Gray’s Inn Road. He became a Hyde Park orator and toyed with the idea of joining an anarchist-communist group. At one of the meetings he was staggered to discover that his long-lost father was the speaker. When the latter disowned him for a second time it was a shattering blow. It ended his association with the anarchists and heralded a dark period in Jack’s life when he became virtually a down-and-out.

Around 1915, however, he fell-in with a well-off widow by the name of Mrs Balbus and was persuaded by her to found a new religion called ‘The Children of the Sun’. Initial meetings were held at her house but as the congregation grew a basement flat was acquired in Charlotte Street in the West End. When this was disbanded he retained the flat which became the home of ‘Professor Curio’s School of Magic’. Entrance was free with nightly lectures and refreshments. The manageress was Mrs J. Neave, Jinny, who he had met when they were sheltering from an air raid during the First World War, and married around 1924.

Jack’s great philosophical mantra, which he adhered to rigidly throughout his life, was that he “worked to live and did not live to work”. Mark Benney, in his 1939 biography of Jack entitled What Rough Beast?, described some of the many and various ways he employed to, as Jack put it, “solve the problem of existence” at this time:

He bought and sold all manner of objects, he read horoscopes, he tipped horses, he interpreted dreams, he hawked cough-cures, he made cheap jewellery, he blended scents. He was to be found conducting credulous strangers on tours through London’s “night-life”; or lecturing, with the aid of a bored chimpanzee, on Evolution and Mormonism. For a short while he drove a flourishing trade in vanishing ink, which he sold to aspiring crooks with the advice that they use it to sign hire-purchase agreements. Again, he had a temporary phase of prosperity when he hit upon the idea of advertising in low journals the sale of “The World’s Most Daring Book on Problems of Sex and Marriage—By More than a Hundred Eminent Authorities”: his description of the Holy Bible which enabled him to sell by mail-order, at five hundred per cent profit, a job-lot he had picked up from a bankrupt missionary society.

The author Pip Granger whose father at one-time rented a flat above the 2I’s coffee bar in Old Compton Street, provided further examples of Jack’s ‘cons’ in her memoir Up West:

He advertised for people to send ten bob…to receive the secret of making money ‘by return of post’. When he got an enquiry, he’d reply promptly with the advice: “Do what I did!” Another scam was to advertise his patent fly killer. Again, on receipt of five shillings …he’d post back two small blocks of wood, one marked ‘A’ and the other ‘B’ and instructions to “Place the fly on block A and whack it hard with block B.”

By these and other means he was able to set-up his ‘School of Wisdom’ in 1931. Musician Jack Glicco (real name: Jacob Gluckstein) recalled this in his 1952 memoir of Soho Madness After Midnight:

The brochure that advertised it promised that lectures would be given on Yoga, Superstition, Graphology, Art, Evolution, Zoroastra and Hypnotism. Jack, who had now added the title “Professor” in front of his name, was the chief tutor, while his instructors placed letters after their names.

The pupils began to flock to the ‘school’ when the word went around that the lecturer on hypnotism could make a woman strip herself naked while under the influence, and that the Art tutor was particularly graphic when instructing his scholars on painting the female body beautiful—and nude.

This enterprise was followed by ‘La Boheme Literary Society’ in a garret high above Charing Cross Road, the ‘Albatross Studio’, the ‘Café Lounge’ and, in the summer of 1934, the ill-fated ‘Caravan Club’ established for lovers of “Art and Beauty”.

When this was raided by the police in August of that year, he was charged at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court with:

“Having on July 25, 26 and 27, unlawfully kept and maintained a place on Endell Street for the purpose of exhibiting to any person willing to pay for admission to the said place, divers lewd, scandalous, bawdy and obscene performances and practices to the manifest corruption of his Majesty’s liege subjects.”

He was committed for trial at the Old Bailey and appeared on September 4, 1934. The trial attracted a great deal of media interest. According to The Times, a police officer, who had attended the club in plain clothes, testified that: “Some men were made up like women and acted like women. One started to dance as a woman would be expected to dance. Men were cuddling and embracing....” Jack, of course, denied that any such dancing took place and a Miss Carmen Fernandez, a professional dancer, called as an “expert witness” by the defence, stated that the Rumba and the Carioca might be thought indecent by those who saw them for the first time. When she was invited by the defence to actually demonstrate the Rumba in front of the dock the judge, Henry Holman Gregory KC, intervened: “there will be nothing of the sort in this court” and, in his final comments, described the club as “A foul den of iniquity which was corrupting the youth of London”.

Naturally Jack was found guilty and sentenced, on October 26, to twenty months hard labour in Wormwood Scrubs. The Daily Express described Jack as a man of striking appearance and, as he went down to the cells to begin his sentence, “the heavy clamp-clamp of his boot could be heard”.

His war years were spent mostly in Oxford and Birmingham but in 1945 he was back in prison, Reading this time, for 8 months, convicted of receiving stolen goods. After his release he took a job as a Father Christmas at the King’s Hall Market in Birmingham. Sometime during the next year his wife Jinny died and, alone, he eventually found his way back to Soho. There he returned to selling charms on the Charing Cross Road and took a stall near Petticoat Lane, adopting an old ruse known as ‘plunder snatching’. For those not in the know, here is Jack’s explanation:

“And here’s the secret: you buy a box of foreign coins and you take these to the Jewel Quarter and you get them gilded. You get a few cheap brass rings, a gross of sewing thimbles, some lucky charms and you get boxes of stones out of broken cheap jewellery (all colours) and bits of broken tin, military badges, jewellery with the stones out and medallions. You muddle all this clutter up on a velvet cloth on your stall and it’s not long before you’ve got a crowd round you sorting it out. You keep shouting out that everything on the board is sixpence, “See what you can find!”

The brochure that advertised it promised that lectures would be given on Yoga, Superstition, Graphology, Art, Evolution, Zoroastra and Hypnotism. Jack, who had now added the title “Professor” in front of his name, was the chief tutor, while his instructors placed letters after their names.

The pupils began to flock to the ‘school’ when the word went around that the lecturer on hypnotism could make a woman strip herself naked while under the influence, and that the Art tutor was particularly graphic when instructing his scholars on painting the female body beautiful—and nude.

This enterprise was followed by ‘La Boheme Literary Society’ in a garret high above Charing Cross Road, the ‘Albatross Studio’, the ‘Café Lounge’ and, in the summer of 1934, the ill-fated ‘Caravan Club’ established for lovers of “Art and Beauty”.

When this was raided by the police in August of that year, he was charged at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court with:

“Having on July 25, 26 and 27, unlawfully kept and maintained a place on Endell Street for the purpose of exhibiting to any person willing to pay for admission to the said place, divers lewd, scandalous, bawdy and obscene performances and practices to the manifest corruption of his Majesty’s liege subjects.”

He was committed for trial at the Old Bailey and appeared on September 4, 1934. The trial attracted a great deal of media interest. According to The Times, a police officer, who had attended the club in plain clothes, testified that: “Some men were made up like women and acted like women. One started to dance as a woman would be expected to dance. Men were cuddling and embracing....” Jack, of course, denied that any such dancing took place and a Miss Carmen Fernandez, a professional dancer, called as an “expert witness” by the defence, stated that the Rumba and the Carioca might be thought indecent by those who saw them for the first time. When she was invited by the defence to actually demonstrate the Rumba in front of the dock the judge, Henry Holman Gregory KC, intervened: “there will be nothing of the sort in this court” and, in his final comments, described the club as “A foul den of iniquity which was corrupting the youth of London”.

Naturally Jack was found guilty and sentenced, on October 26, to twenty months hard labour in Wormwood Scrubs. The Daily Express described Jack as a man of striking appearance and, as he went down to the cells to begin his sentence, “the heavy clamp-clamp of his boot could be heard”.

His war years were spent mostly in Oxford and Birmingham but in 1945 he was back in prison, Reading this time, for 8 months, convicted of receiving stolen goods. After his release he took a job as a Father Christmas at the King’s Hall Market in Birmingham. Sometime during the next year his wife Jinny died and, alone, he eventually found his way back to Soho. There he returned to selling charms on the Charing Cross Road and took a stall near Petticoat Lane, adopting an old ruse known as ‘plunder snatching’. For those not in the know, here is Jack’s explanation:

“And here’s the secret: you buy a box of foreign coins and you take these to the Jewel Quarter and you get them gilded. You get a few cheap brass rings, a gross of sewing thimbles, some lucky charms and you get boxes of stones out of broken cheap jewellery (all colours) and bits of broken tin, military badges, jewellery with the stones out and medallions. You muddle all this clutter up on a velvet cloth on your stall and it’s not long before you’ve got a crowd round you sorting it out. You keep shouting out that everything on the board is sixpence, “See what you can find!”

Now you don’t put the gilded coins on in a large quantity. You put a few on at a time, five or six, and these will sell quite well because there’s a lot of people silly enough to think that you’re silly enough to accidentally allow a solid gold coin to be on the stall. The people who buy these gold coins, thinking that they’ve bought a gold coin, they run away as fast as they can. That’s “plunder snatching”.”

This would have been a precarious existence, however, were it not for the introduction of National Assistance after the war, and Jack, in his early seventies, was able to apply for a pension:

“I will say this: that I thank the makers of the Welfare State who have given people like me, who live a precarious life, a pension at seventy, because it prevents us from becoming tramps. No matter what fiddling game we were at, we could never earn the money to pay for a furnished room and most lodging-houses are, at the very least, two shillings or a half-a-crown a night….However, the pension has solved the problem. It pays for a shelter and all I have to do is to get money for food. I get plenty of clothes given to me and I have got a very nice collection of cravats and collars, and about twelve books which I cherish. And I’m not short of company: I’ve got several people…who visit me and I’m not short of the company of beautiful women either—they seem to like my companionship.”

Toward the end of his life he was often to be found in the French café in Old Compton Street, where the proprietor allowed him to sit for three or four hours and talk to the students from the nearby St Martin’s Art School. He became a celebrity model, posing for the students. This became a regular event and helped to further supplement his income. It was here that he met, among others, Quentin Crisp…

During the first Soho Festival—from July 10th-16th, 1956—Jack performed ‘Cockney Songs and Ballads’ with a character called Black Larry in Golden Square. The week ended with a massive party (as reported in the Soho Weekly Reporter):

“Wildest Party Seen in Soho…

What a night—such a night—it really was. Three hundred, singing, laughing, living (im)mortals crowded into Old Compton Street parking-lot last Saturday night to blow out the lanterns of the first Soho Fair. Soho characters launched themselves into Bohemia’s wildest of wild, wild parties. The merry-making was officially declared open by Ironfoot Jack, who this night added the brightest of jewels to his Bohemian crown.

Here was the true spirit of Soho. A little trouble here and there—due mainly to gate crashers—which brought the police out in strength. A prematurely lit bonfire which dragged the Brigade out into the night air, but nothing except an occasional cracked head that the ‘Bums’ could be ashamed of.

“The police were wonderful,” said a ‘Bum’ chief.

“The characters were very good,” reported a police spokesman.

So with gaiety and good-will, the first Soho Fair ended about 3 a.m. on Sunday morning.”

This would have been a precarious existence, however, were it not for the introduction of National Assistance after the war, and Jack, in his early seventies, was able to apply for a pension:

“I will say this: that I thank the makers of the Welfare State who have given people like me, who live a precarious life, a pension at seventy, because it prevents us from becoming tramps. No matter what fiddling game we were at, we could never earn the money to pay for a furnished room and most lodging-houses are, at the very least, two shillings or a half-a-crown a night….However, the pension has solved the problem. It pays for a shelter and all I have to do is to get money for food. I get plenty of clothes given to me and I have got a very nice collection of cravats and collars, and about twelve books which I cherish. And I’m not short of company: I’ve got several people…who visit me and I’m not short of the company of beautiful women either—they seem to like my companionship.”

Toward the end of his life he was often to be found in the French café in Old Compton Street, where the proprietor allowed him to sit for three or four hours and talk to the students from the nearby St Martin’s Art School. He became a celebrity model, posing for the students. This became a regular event and helped to further supplement his income. It was here that he met, among others, Quentin Crisp…

During the first Soho Festival—from July 10th-16th, 1956—Jack performed ‘Cockney Songs and Ballads’ with a character called Black Larry in Golden Square. The week ended with a massive party (as reported in the Soho Weekly Reporter):

“Wildest Party Seen in Soho…

What a night—such a night—it really was. Three hundred, singing, laughing, living (im)mortals crowded into Old Compton Street parking-lot last Saturday night to blow out the lanterns of the first Soho Fair. Soho characters launched themselves into Bohemia’s wildest of wild, wild parties. The merry-making was officially declared open by Ironfoot Jack, who this night added the brightest of jewels to his Bohemian crown.

Here was the true spirit of Soho. A little trouble here and there—due mainly to gate crashers—which brought the police out in strength. A prematurely lit bonfire which dragged the Brigade out into the night air, but nothing except an occasional cracked head that the ‘Bums’ could be ashamed of.

“The police were wonderful,” said a ‘Bum’ chief.

“The characters were very good,” reported a police spokesman.

So with gaiety and good-will, the first Soho Fair ended about 3 a.m. on Sunday morning.”

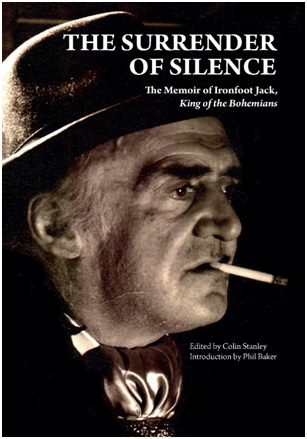

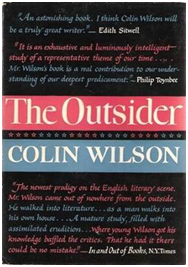

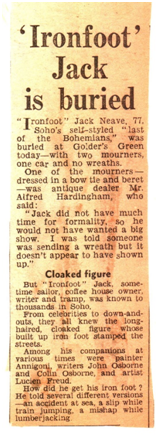

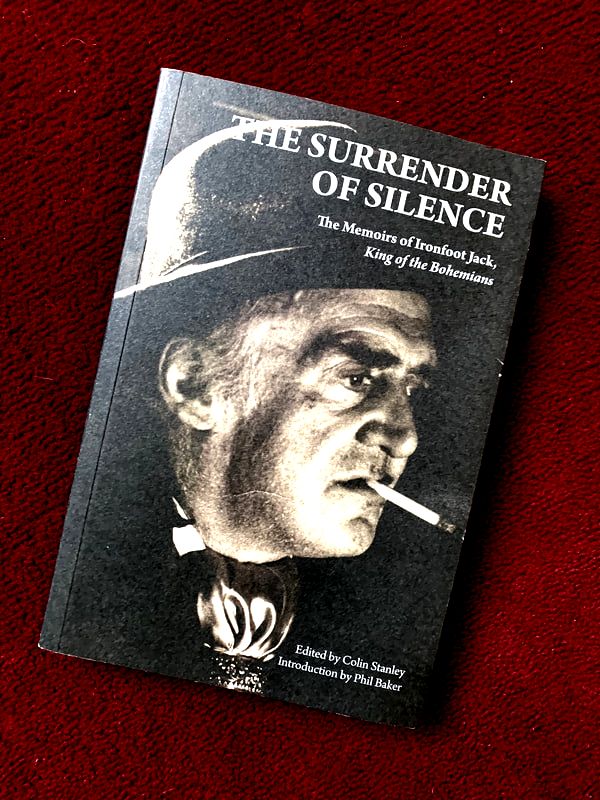

I understand from the artist Timothy Whidborne that, during the many sessions he spent with Jack when painting his portrait in the mid-1950s, he dictated his memoir The Surrender of Silence onto a tape recorder. Arrangements were then made, by Whidborne’s secretary, for the manuscript to be typed. The original was retained by Whidborne who undertook to try and find a publisher. Jack was given the carbon copy which he carried around with him in his bag before entrusting it, in 1957, to the author Colin Wilson whose book The Outsider (London: Victor Gollancz) had been one of the sensations of 1956. The manuscript concentrates mainly on the period following his release from Wormwood Scrubs: the Second World War and afterwards until 1956. He died on September 29, 1959 at St Columba’s Hospital in Hampstead, aged 77. His funeral took place at Hampstead Cemetery on October 7th.

Colin Wilson and Ironfoot Jack:

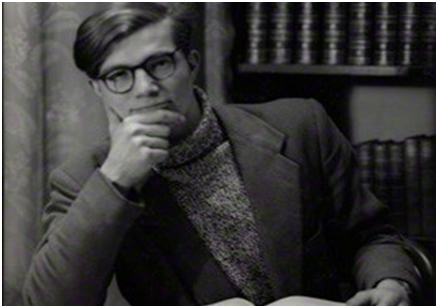

In 2009 the University of Nottingham acquired my vast collection of the printed works of the English existentialist philosopher and author Colin Wilson. As his bibliographer I had built-up the collection over more than three decades and it had become too big for my house to accommodate. A few years before his death in 2013 I suggested to him, and his wife Joy, that they consider depositing his papers and manuscripts at the same location with the aim of creating a centre for the study of his work and, in the summer of 2012, the first tranche of around eighty manuscripts, and several files of correspondence, were transferred from their home in Cornwall to the safety of the Manuscripts and Special Collections store at the University.

In the ensuing years I have continued the task of sorting, and making ready for transfer, nearly sixty years of Colin Wilson’s work: papers, journals, correspondence and manuscripts, including the handwritten manuscript of The Outsider, one of the most iconic books of the twentieth century.

I was intrigued to find, among his papers, the carbon copy of Ironfoot Jack’s manuscript The Surrender of Silence along with a folder containing photographs, press cuttings and letters. Some of these letters are reproduced in Appendix 3 of the book and they reveal that Jack, having completed his manuscript in 1956, left it with Colin, sometime in 1957, in the hope that he could find a publisher for it. Naturally Colin turned first to his own publisher Victor Gollancz who, judging by a rather curt note scribbled on a compliments slip, was not at all impressed. In 1960, shortly after Jack’s death, the manuscript was in the hands of Skelton Robinson Limited, a London publisher who were keen enough to send it out to an editor. The many handwritten corrections and suggestions that appear on the manuscript date from this time. Unfortunately, Skelton Robinson ceased trading in 1961 and so Colin’s efforts were thwarted. With Jack deceased, and therefore no longer able to benefit financially from the project (he had hoped that royalties from its publication would supply him with a comfortable old-age), the incentive to find a publisher was gone. I presume Colin, understandably, set it aside to concentrate on his own work.

Colin Wilson and Ironfoot Jack:

In 2009 the University of Nottingham acquired my vast collection of the printed works of the English existentialist philosopher and author Colin Wilson. As his bibliographer I had built-up the collection over more than three decades and it had become too big for my house to accommodate. A few years before his death in 2013 I suggested to him, and his wife Joy, that they consider depositing his papers and manuscripts at the same location with the aim of creating a centre for the study of his work and, in the summer of 2012, the first tranche of around eighty manuscripts, and several files of correspondence, were transferred from their home in Cornwall to the safety of the Manuscripts and Special Collections store at the University.

In the ensuing years I have continued the task of sorting, and making ready for transfer, nearly sixty years of Colin Wilson’s work: papers, journals, correspondence and manuscripts, including the handwritten manuscript of The Outsider, one of the most iconic books of the twentieth century.

I was intrigued to find, among his papers, the carbon copy of Ironfoot Jack’s manuscript The Surrender of Silence along with a folder containing photographs, press cuttings and letters. Some of these letters are reproduced in Appendix 3 of the book and they reveal that Jack, having completed his manuscript in 1956, left it with Colin, sometime in 1957, in the hope that he could find a publisher for it. Naturally Colin turned first to his own publisher Victor Gollancz who, judging by a rather curt note scribbled on a compliments slip, was not at all impressed. In 1960, shortly after Jack’s death, the manuscript was in the hands of Skelton Robinson Limited, a London publisher who were keen enough to send it out to an editor. The many handwritten corrections and suggestions that appear on the manuscript date from this time. Unfortunately, Skelton Robinson ceased trading in 1961 and so Colin’s efforts were thwarted. With Jack deceased, and therefore no longer able to benefit financially from the project (he had hoped that royalties from its publication would supply him with a comfortable old-age), the incentive to find a publisher was gone. I presume Colin, understandably, set it aside to concentrate on his own work.

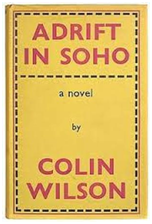

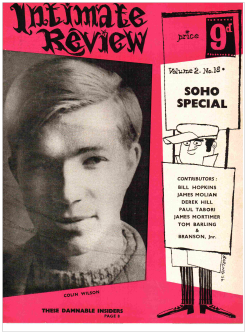

Colin Wilson first came to London in June 1951 (5 years before he became a household name after the publication of his first book The Outsider) and was sometimes to be found around Soho. Here he met and befriended several other budding writers: Bill Hopkins (1928-2011), Stuart Holroyd (1933-), Alexander Trocchi (1925-1984), Laura Del Rivo (1934-) and the poet John Rety (1930-2010) who edited the coffee-bar literary magazine The Intimate Review, famously Colin’s first publisher.

He must have met Ironfoot Jack at this time because Jack was very much a celebrity figure. Also in Soho, Colin met an out-of-work actor by the name of Charles Belchier (aka Russell), a Bohemian, whose memoir The Other Side of Town, was adapted by Colin into Part One of his 1961 novel Adrift in Soho. Jack features in both Belchier’s memoir and Colin’s novel. Indeed he is the only character in the novel to retain his real name. In The Other Side of Town, Jack is to be found in the Wheatsheaf pub, Rathbone Place (still in existence) and later the Café Alex in Soho: “His black cloak and inevitable high-collared cravat gave him the air of a Mephistophelian Santa Claus.”

Colin Wilson had originally intended to dedicate Adrift in Soho to Jack but was dissuaded from doing so, possibly by Gollancz, and the novel was dedicated instead to ‘James’ i.e. Charles Belchier, who features in the novel as James Compton Street. The hero is Harry Preston, a young man very much like Colin himself, who had newly arrived in London from the provinces:

“An hour later, I sat in a café in Old Compton Street and drank tea….I was watching an old man who sat at a table in the corner, snipping bits of brass wire and making them into ear-rings by hanging beads on them and twisting them expertly with a pair of pliers. He had a broad, good natured face and long grey hair that hung down to his shoulders, and he wore what seemed to be a very old and tattered cloak over his shoulders. From his concentration on his task, I presumed he was one of those taciturn men whose eccentricity is a sign of complete indifference to society…. (It was only later that I learned I could not have been more mistaken in my idea of his character.)” (Adrift in Soho. London: Pan Books, 1964, p. 40)

A few pages later, Jack is introduced to Harry when he gate-crashes the hilarious scene in Osky’s kitchen-less fish and chip ‘restaurant’. The idea for this scene was almost certainly gleaned from Jack himself who says in The Surrender of Silence that he had heard that such an establishment had actually existed at one time. Pip Granger asserted that Jack, at one time, actually ran such an establishment:

He rented a semi-derelict building where the electricity had been cut off. Undaunted, Jack arranged to have paraffin lamps liberated from local night-watchmen, and lit the place with those. Impressive menus were provided, in French no less, to add a little class, but every item on them, bar one, was crossed out due to ‘shortages’ and ‘rationing’. The one dish left was ‘poisson et pommes frites’. When the diners duly ordered, Jack would yell the order into the non-existent kitchen and ‘a lad’ would sprint down to the nearest chippie, grab the requisite portions of fish and chips, sprint back, dump them on plates and then Jack, with the great dignity of a seasoned maître d’hôtel, would serve them…

Daniel Farson (1927-1997) included that story in his Soho in the Fifties (London: Michael Joseph Ltd, 1987) but doubted its veracity. Dan, however, was one of the ‘new generation’ of post-war Sohoites who considered Jack to be “…a dreadful old bore….” George Melly (1926-2007), in the second part of his autobiography, Rum, Bum and Concertina (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977), concurred adding: “He had a juicy Cockney accent, boasted of occult powers and lived with a series of old crones whom he used as an excuse for hinting at a Crowleyian sexual virility.”

Despite these inevitable put-downs by a ‘younger’ generation, The Surrender of Silence stands as a remarkable document of a way of life that has gone forever: “It will be a sensation to modern society how the other half lived in those dreamy days gone by…” he wrote in a letter to Colin Wilson. Indeed, it is difficult to think how anyone could make such a living today.

After World War Two, and the introduction of the Welfare State, Jack could see the writing on the wall: “The last World War shattered everything: Bohemian cafés, five shilling a week basements and cellars, camping out on London Commons. Those days are over now…and I do not think that situation will develop again….” By the 1950s most of the characters that he wrote about had gone: many were killed in the air raids, others drifted away from a Soho that was changing rapidly. Jack, however, stayed true to his calling…right up to the end, despite his faults, an earnest, resourceful and kindly man:

Colin Wilson had originally intended to dedicate Adrift in Soho to Jack but was dissuaded from doing so, possibly by Gollancz, and the novel was dedicated instead to ‘James’ i.e. Charles Belchier, who features in the novel as James Compton Street. The hero is Harry Preston, a young man very much like Colin himself, who had newly arrived in London from the provinces:

“An hour later, I sat in a café in Old Compton Street and drank tea….I was watching an old man who sat at a table in the corner, snipping bits of brass wire and making them into ear-rings by hanging beads on them and twisting them expertly with a pair of pliers. He had a broad, good natured face and long grey hair that hung down to his shoulders, and he wore what seemed to be a very old and tattered cloak over his shoulders. From his concentration on his task, I presumed he was one of those taciturn men whose eccentricity is a sign of complete indifference to society…. (It was only later that I learned I could not have been more mistaken in my idea of his character.)” (Adrift in Soho. London: Pan Books, 1964, p. 40)

A few pages later, Jack is introduced to Harry when he gate-crashes the hilarious scene in Osky’s kitchen-less fish and chip ‘restaurant’. The idea for this scene was almost certainly gleaned from Jack himself who says in The Surrender of Silence that he had heard that such an establishment had actually existed at one time. Pip Granger asserted that Jack, at one time, actually ran such an establishment:

He rented a semi-derelict building where the electricity had been cut off. Undaunted, Jack arranged to have paraffin lamps liberated from local night-watchmen, and lit the place with those. Impressive menus were provided, in French no less, to add a little class, but every item on them, bar one, was crossed out due to ‘shortages’ and ‘rationing’. The one dish left was ‘poisson et pommes frites’. When the diners duly ordered, Jack would yell the order into the non-existent kitchen and ‘a lad’ would sprint down to the nearest chippie, grab the requisite portions of fish and chips, sprint back, dump them on plates and then Jack, with the great dignity of a seasoned maître d’hôtel, would serve them…

Daniel Farson (1927-1997) included that story in his Soho in the Fifties (London: Michael Joseph Ltd, 1987) but doubted its veracity. Dan, however, was one of the ‘new generation’ of post-war Sohoites who considered Jack to be “…a dreadful old bore….” George Melly (1926-2007), in the second part of his autobiography, Rum, Bum and Concertina (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977), concurred adding: “He had a juicy Cockney accent, boasted of occult powers and lived with a series of old crones whom he used as an excuse for hinting at a Crowleyian sexual virility.”

Despite these inevitable put-downs by a ‘younger’ generation, The Surrender of Silence stands as a remarkable document of a way of life that has gone forever: “It will be a sensation to modern society how the other half lived in those dreamy days gone by…” he wrote in a letter to Colin Wilson. Indeed, it is difficult to think how anyone could make such a living today.

After World War Two, and the introduction of the Welfare State, Jack could see the writing on the wall: “The last World War shattered everything: Bohemian cafés, five shilling a week basements and cellars, camping out on London Commons. Those days are over now…and I do not think that situation will develop again….” By the 1950s most of the characters that he wrote about had gone: many were killed in the air raids, others drifted away from a Soho that was changing rapidly. Jack, however, stayed true to his calling…right up to the end, despite his faults, an earnest, resourceful and kindly man:

“I have written The Surrender of Silence not so much for my material gain but to the memory of a glorious past of Bohemian life which is now gone… leaving behind only memories and a brief spell of passion and strife….”

You may not consider it to be the “sensation” that Jack predicted but, at the very least, it’s an extraordinary and highly entertaining adventure story.

Despite George Melly’s disparaging remarks quoted earlier, he did provide a generous caption when Timothy Whidborne’s portrait of Jack was exhibited in the window of Foyles Bookshop during the Soho Festival in 1956:

“Carrying his worldly belongings on his back, his pockets bulging with yellowing pages of occult symbols, the figure of Ironfoot Jack passes through the streets of London, behind him, the Bohemian phantoms of a bygone era materialise. The chromium and neon of Wardour Street vanish, and under the gaslights a cab horse waits for a forgotten poet.”

And the final word goes to Whidborne himself from his ‘Ballad of Ironfoot Jack’:

“Here in the heart of London town

The swirling fog lies thick,

One hears some faltering footsteps

And the tapping of a stick

Limping down the streets of Soho

Comes a figure dressed in black

It’s the legendary hero

The old Bohemian Ironfoot Jack”

You may not consider it to be the “sensation” that Jack predicted but, at the very least, it’s an extraordinary and highly entertaining adventure story.

Despite George Melly’s disparaging remarks quoted earlier, he did provide a generous caption when Timothy Whidborne’s portrait of Jack was exhibited in the window of Foyles Bookshop during the Soho Festival in 1956:

“Carrying his worldly belongings on his back, his pockets bulging with yellowing pages of occult symbols, the figure of Ironfoot Jack passes through the streets of London, behind him, the Bohemian phantoms of a bygone era materialise. The chromium and neon of Wardour Street vanish, and under the gaslights a cab horse waits for a forgotten poet.”

And the final word goes to Whidborne himself from his ‘Ballad of Ironfoot Jack’:

“Here in the heart of London town

The swirling fog lies thick,

One hears some faltering footsteps

And the tapping of a stick

Limping down the streets of Soho

Comes a figure dressed in black

It’s the legendary hero

The old Bohemian Ironfoot Jack”